I've begun working on the first TESS story module, tentatively titled "In Enemy Territory." I thought I'd share my process for creating these type of branching-path gamebooks. It's probably not the most efficient way to do it, but it's worked for me on multiple projects.

I work with two different documents--usually a Microsoft Word and a Microsoft Office document, although Google Docs works fine if I want to be able to work from any computer.

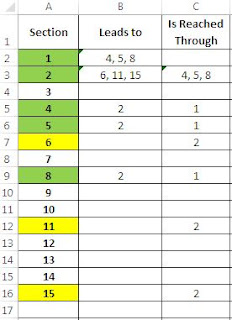

I use a spreadsheet to track each section in the gamebook.

The first column just has each section in order. In some of my (as-yet unreleased) projects, I may break the story into different chapters, each with multiple numbered sections, such as Chapter 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, et cetera. In "In Enemy Territory," I think I'll just use numbered sections without chapters--probably between 100 and 150 sections.

Whenever I write and finish a section, I'll highlight it in green. Then I mark in column two which section or section the player can go to from there. For example, section 1 leads to sections 4, 5, or 8.

If a section has a branch that leads to it and has not yet been written, I highlight it in yellow. You can see that section 2 leads to section 6, 11, and 15, none of which have been written yet.

The third column tracks which section or sections lead to a particular branch. Section 1 is the only way to get to section 5, for example. This helps me if I ever need to backtrack--I can quickly follow the trail backwards, all the way to the beginning of the game if necessary.

You can see the first little bit of the story here. Bear in mind that this is an early draft. I have not, for example, figured out exactly how I want to present the encounters. Still, it might be interesting to see the process.

Popular Posts

-

THE IRONCLAD The Ironclad has, in my opinion, the strongest starting relic in the game. Burning Blood heals the Ironclad for 6 HP after ea...

Sunday, August 25, 2013

Monday, August 19, 2013

Privyet, Russia!

I just discovered that this blog gets a lot of views from Russia. So, shout out to all my Russian readers! Я уверен, что вы все очень крутиe людей!

I lived in Russia for a couple years, so please don't hesitate to post any questions or comments по-русский.

I lived in Russia for a couple years, so please don't hesitate to post any questions or comments по-русский.

Sunday, August 18, 2013

Brainstorming, Continued: The First TESS Story

The basic mechanics of the game are starting to come together in my head. We're rapidly approaching the point where I need to start putting together a prototype. To do that, I need to put together a story for the player to play through.

I'd like the first TESS (The Expandable Solitaire System) story to put the player through a series of challenges that require different foci. I don't want everything to be combat-based, so that a combat-heavy deck can just waltz through it. That means there should be some hacking, some social encounters, perhaps some environmental challenges.

I'd also love to be able to incorporate three act structure into the narrative. This is a finely tuned narrative skeleton. When applied correctly, it gives the audience a compelling narrative with a satisfactory climax and denouement. The structure was used, completely on accident, to great success for several decades before film critics and theorists were finally able to nail down what the good films were doing that worked so well.

The first act of the story introduces the main characters and the world they inhabit. It also sets up the status quo. Now, the status quo may be lousy, such as in Star Wars--everybody is under the thumb of the Empire. Then there is an inciting incident, an event that compels the hero (or heroes) to action. Often, the hero has no idea that this action will change the course of his or her life. In Star Wars, Luke just goes off into the desert to find his uncle's rogue droid. Act one ends with a major plot point that propels the story into a new direction--Luke agrees to go with Ben Kenobi, Neo takes the red pill, the Avengers assemble to help Nick Fury, Dorothy sets off to see the Wizard, etc.

In the second act--which takes up the bulk of the story--there is a great deal of action as the story accelerates. The hero learns new skills and gains new allies. However, things keep getting worse and worse for the hero. At the midpoint, it seems that all hope is lost! The heroes are about to be smashed by a garbage compactor; the team has been scattered and/or killed; there's a traitor in the midst; things just could not get any worse! Then things begin to turn around. The heroes reunite. The major plot point from the first act is (usually) resolved--the princess is rescued, Loki's plan is discovered, Neo accepts his role in the Matrix and rescues Morpheus, and so forth. But a new plot point comes along that propels into the final climactic act--the Death Star is about to wipe out the Rebellion, Loki opens the portal, Neo decides to fight Agent Smith, Dorothy must confront the Wicked Witch.

The third and final act includes the final battle, where the hero must use the skills he or she has learned and rely on the new friends he or she has gained in order to triumph. Han saves Luke's bacon, then Luke uses the Force to blow up the Death Star. Neo becomes faster and stronger than an Agent. The Avengers work together to blow up the Chitauri forces and shut the portal. Dorothy is rescued by her friends and melts the witch.

So how can we incorporate these lessons into our TESS narrative? First, let's ask some questions about the characters and setting.

Who is the hero? Well, for the first TESS story, it should be the player. (There's room to play here, of course. It is entirely possible for the player to play Han to the story's Luke, but let's not meddle with the formula until after we've perfected the formula.) The player can be a robot, a cyborg, a human, or an uplift. That does make things a little difficult; each Persona has different goals, perspectives, and desires.

What does the main character want? Let's borrow from Serenity for a moment and say, "Freedom." No matter what Persona the player is using, the character's goal is to be free. He or she has a starship and a steady enough income to keep it running. He or she may have a dark past that is constantly trying to catch up with him or her--we'll see how things develop.

What problem does the main character have? Now we get to the inciting incident. Uh oh, there's a problem with the ship! Better land and get your ship repaired. But this is our inciting incident, after all; it can't be as easy as, "Okay, your ship will be fixed in an hour. That will be $100." So there's a problem with acquiring it. Maybe the city has recently been attacked? The port was raided, and the mechanic cannot repair your ship right away. But perhaps if you acquired the part you need? He tells you of the enemy's base, and says that if you bring back the part you need and some spare parts for him, he'll repair your ship free of charge.

You agree. That's the first plot point.

Time to sneak into an enemy base.

There will be some opportunities, at this point, to overcome some combat, hacking, and environmental challenges. The base is surrounded by an electric fence and you need to get passed it. You encounter some guards and need to take them down. The door is locked and you need to bypass it. The storage location for spare ship parts is hidden and you need to hack a computer terminal to find out where they are. Et cetera.

Now, we need a good midpoint. A classic one would be to have the hero captured. You're stripped of your equipment and thrown into a cell until the interrogator can arrive. You mount a daring escape, retrieve your equipment, steal the parts, and return to the port for your ship repairs. However, as the mechanic is working on your ship, your conscience nags at you. The things that were happening at the enemy base were despicable, inhuman. Can you really just leave these people to their fate?

Of course you can't! You decide to help out. That's the second plot point that drives us into the third act. You gear up and head out to bring down the enemies, using your knowledge of the layout of their base to pick them apart. Eventually, you reach Weak Point X and use it to wipe out the enemy base, but not before a final climactic battle with the Big Bad Guy and the Evil Mastermind.

Now, obviously, there are some important points to flesh out. Who are the enemies? What are they trying to accomplish? What does the hero see that spurns him or her to action? But this is a nice, simple plot outline that I can work with. It allows for several different types of encounters--Social, Combat, Hacking, and Environmental. It has a beginning, middle, and end, with a nice character arc thrown in for good measure. I can flesh out the details as I write the story, but this is a solid guide for what, in general, needs to happen.

Thanks for reading! I'm always up for a good discussion about films and the three-act structure, so feel free to post questions or comments.

I'd like the first TESS (The Expandable Solitaire System) story to put the player through a series of challenges that require different foci. I don't want everything to be combat-based, so that a combat-heavy deck can just waltz through it. That means there should be some hacking, some social encounters, perhaps some environmental challenges.

I'd also love to be able to incorporate three act structure into the narrative. This is a finely tuned narrative skeleton. When applied correctly, it gives the audience a compelling narrative with a satisfactory climax and denouement. The structure was used, completely on accident, to great success for several decades before film critics and theorists were finally able to nail down what the good films were doing that worked so well.

The first act of the story introduces the main characters and the world they inhabit. It also sets up the status quo. Now, the status quo may be lousy, such as in Star Wars--everybody is under the thumb of the Empire. Then there is an inciting incident, an event that compels the hero (or heroes) to action. Often, the hero has no idea that this action will change the course of his or her life. In Star Wars, Luke just goes off into the desert to find his uncle's rogue droid. Act one ends with a major plot point that propels the story into a new direction--Luke agrees to go with Ben Kenobi, Neo takes the red pill, the Avengers assemble to help Nick Fury, Dorothy sets off to see the Wizard, etc.

In the second act--which takes up the bulk of the story--there is a great deal of action as the story accelerates. The hero learns new skills and gains new allies. However, things keep getting worse and worse for the hero. At the midpoint, it seems that all hope is lost! The heroes are about to be smashed by a garbage compactor; the team has been scattered and/or killed; there's a traitor in the midst; things just could not get any worse! Then things begin to turn around. The heroes reunite. The major plot point from the first act is (usually) resolved--the princess is rescued, Loki's plan is discovered, Neo accepts his role in the Matrix and rescues Morpheus, and so forth. But a new plot point comes along that propels into the final climactic act--the Death Star is about to wipe out the Rebellion, Loki opens the portal, Neo decides to fight Agent Smith, Dorothy must confront the Wicked Witch.

The third and final act includes the final battle, where the hero must use the skills he or she has learned and rely on the new friends he or she has gained in order to triumph. Han saves Luke's bacon, then Luke uses the Force to blow up the Death Star. Neo becomes faster and stronger than an Agent. The Avengers work together to blow up the Chitauri forces and shut the portal. Dorothy is rescued by her friends and melts the witch.

So how can we incorporate these lessons into our TESS narrative? First, let's ask some questions about the characters and setting.

Who is the hero? Well, for the first TESS story, it should be the player. (There's room to play here, of course. It is entirely possible for the player to play Han to the story's Luke, but let's not meddle with the formula until after we've perfected the formula.) The player can be a robot, a cyborg, a human, or an uplift. That does make things a little difficult; each Persona has different goals, perspectives, and desires.

What does the main character want? Let's borrow from Serenity for a moment and say, "Freedom." No matter what Persona the player is using, the character's goal is to be free. He or she has a starship and a steady enough income to keep it running. He or she may have a dark past that is constantly trying to catch up with him or her--we'll see how things develop.

What problem does the main character have? Now we get to the inciting incident. Uh oh, there's a problem with the ship! Better land and get your ship repaired. But this is our inciting incident, after all; it can't be as easy as, "Okay, your ship will be fixed in an hour. That will be $100." So there's a problem with acquiring it. Maybe the city has recently been attacked? The port was raided, and the mechanic cannot repair your ship right away. But perhaps if you acquired the part you need? He tells you of the enemy's base, and says that if you bring back the part you need and some spare parts for him, he'll repair your ship free of charge.

You agree. That's the first plot point.

Time to sneak into an enemy base.

There will be some opportunities, at this point, to overcome some combat, hacking, and environmental challenges. The base is surrounded by an electric fence and you need to get passed it. You encounter some guards and need to take them down. The door is locked and you need to bypass it. The storage location for spare ship parts is hidden and you need to hack a computer terminal to find out where they are. Et cetera.

Now, we need a good midpoint. A classic one would be to have the hero captured. You're stripped of your equipment and thrown into a cell until the interrogator can arrive. You mount a daring escape, retrieve your equipment, steal the parts, and return to the port for your ship repairs. However, as the mechanic is working on your ship, your conscience nags at you. The things that were happening at the enemy base were despicable, inhuman. Can you really just leave these people to their fate?

Of course you can't! You decide to help out. That's the second plot point that drives us into the third act. You gear up and head out to bring down the enemies, using your knowledge of the layout of their base to pick them apart. Eventually, you reach Weak Point X and use it to wipe out the enemy base, but not before a final climactic battle with the Big Bad Guy and the Evil Mastermind.

Now, obviously, there are some important points to flesh out. Who are the enemies? What are they trying to accomplish? What does the hero see that spurns him or her to action? But this is a nice, simple plot outline that I can work with. It allows for several different types of encounters--Social, Combat, Hacking, and Environmental. It has a beginning, middle, and end, with a nice character arc thrown in for good measure. I can flesh out the details as I write the story, but this is a solid guide for what, in general, needs to happen.

Thanks for reading! I'm always up for a good discussion about films and the three-act structure, so feel free to post questions or comments.

Saturday, August 17, 2013

Brainstorming, Continued: Multiple Axes of Decision

The brainstorming phase of game creation is an exciting time. You get to throw dozens, perhaps hundreds of ideas against the wall and see which ones stick. (The cleanup afterwards isn't fun, but that's why they invented industrial-strength vacuums.)

A loose design goal I had for this game was to make it playable with just the rulebook, a story book, and the cards. The main reason for this goal was to cut down on the barrier between player and game. With print-and-play games, any addition of components just makes it that much harder for players to jump in and try the game. "Sorry, not only do you need to print and cut 200 cards, but you have to acquire 30 Eurocubes in assorted colors, and at least 10 dice of two different colors." That's a hassle. It's daunting to a lot of would-be PnPers. So I try to lower the barrier to entry to my PnP games as much as possible.

But, for the good of the game, I going to add at least one new dimension. Resources.

In previous brainstorming sessions, it was determined that the player would have a hand of cards, a deck of cards, and a discard pile as resources from which they could attempt to overcome various challenges. The problem with this is that it's binary. You either have the card(s) that you need or you do not. That's not an interesting game. ESPECIALLY when I'd like to give the player the chance to dig for the card(s) he or she needs.

What would make the game more interesting was to force the player to balance short- and long-term benefits. Sure, you can defeat that squad of mercenaries now, but will that leave you helpless in the robot boss fight later? Can you absorb the damage from the turret in order to save up for the final hacking challenge? This tension creates much more interesting game decisions. So how do I add this tension to the game?

The answer is to give the cards a cost in Resources. Yes, you can fire that Grenade Launcher now, but will that leave you enough cash to use your weapons later in the game? Sure, you can trade some intell to get a tool you need, but then what will you use to break into the data fortress? Those are the kinds of decisions I want the players to be making!

Currently, I think the game only needs two types of Resources: Cash and Data. Using physical Items will typically have a cost in Cash, while performing certain actions such as hacking or convincing might require Data. Some cards might require both, and the occasional card may cost neither. The important thing is that the player will now have multiple axes of decision. It will not just be a case of having the right cards, but using those cards effectively to maintain a pool of Resources.

The downside to this is that the player will need a way to track his or her Resources, whether it be pen and paper, a smart phone app, an Excel sheet, poker chips, or whatever they have on hand. It increases the game's footprint (more space require on the table in order to play) and ratchets up the barrier to entry, if only slightly. Still, I think this will be an important step in making the kind of dynamic and interesting solitaire game system that this needs to be.

I am also considering a third layer, in addition to cards and Resources: Actions. During an encounter, the player would be able to perform X number of Actions, and then the encounter would "act." This may mean doing something detrimental to the player, such as forcing him or her to discard cards or lose Resources, or it could just advance some sort of timer--a countdown to something really bad happening. This has the added benefit of balancing out the ability to discard a card and draw a card. If the player can only take, say, three actions before the encounter acts, it's potentially a lot more costly to need five actions just to find the cards necessary to guarantee success. More importantly, this would give encounters a more dynamic feel, with a "back-and-forth" dynamic happening between the player and the game's AI.

This would mean that encounters would be more difficult to create and balance. That's more work on the part of the designer, and I'm not certain yet if the game needs this sort of dynamic. But it does make for more interesting outcomes to the encounters beyond simply pass/fail. And it would give the player another axis of decision, and another knob for the designer to tweak while trying to balance the game and increase the tension and fun. I'll keep it on the back burner for now, but I like the idea.

Sunday, August 11, 2013

Brainstorming, Continued: Building a Skeleton

With this contest, I'd really like to show my design methods as much as possible. Not only do I think that it might--MIGHT, mind you--be interesting and instructive to others, but it will be a good resource for myself. I can analyze what I do and why I do it, which will hopefully lead to improvements in my own methodology.

As demonstrated in the previous post, my preferred method is to brainstorm a variety of ideas, then use deductive logic to eliminate the weaker ideas. We now have a very basic shape or outline of the game. It's time now to build a skeleton. We'll put some meat on the bones later, but for now we just want a good sturdy structure on which to build.

The game requires the construction of three major components: the rules, the stories, and the customizable decks. The game cannot function without all three components, so we must always keep these three aspects in mind as we put our skeleton together.

Before the player begins a game, he or she must construct a deck. (I'm assuming they have gone through the process of building or purchasing the components and are familiar with the rules.) Of what does deckbuilding consist?

Well, first they must select a Persona. I find the idea of four separate and distinct Personas to be very balanced and pleasing. This means that there should be at least four different thematic strategies for approaching the game. Let's explore those briefly.

As demonstrated in the previous post, my preferred method is to brainstorm a variety of ideas, then use deductive logic to eliminate the weaker ideas. We now have a very basic shape or outline of the game. It's time now to build a skeleton. We'll put some meat on the bones later, but for now we just want a good sturdy structure on which to build.

The game requires the construction of three major components: the rules, the stories, and the customizable decks. The game cannot function without all three components, so we must always keep these three aspects in mind as we put our skeleton together.

Before the player begins a game, he or she must construct a deck. (I'm assuming they have gone through the process of building or purchasing the components and are familiar with the rules.) Of what does deckbuilding consist?

Well, first they must select a Persona. I find the idea of four separate and distinct Personas to be very balanced and pleasing. This means that there should be at least four different thematic strategies for approaching the game. Let's explore those briefly.

- Human - Humans are (relatively) physically weak, with shaky limbs and poor eyesight. This means that they struggle in combat unless they have the correct tools for the job. However, they are very good at ACQUIRING the correct tools for the job. Human cards should focus on digging through the deck, manipulating cards in hand, sifting through the discard pile, and maybe even pulling cards back from exile. Humans are innovators, using creativity and planning to overcome the obstacles they encounter. They are also very adept at social challenges, particularly since they almost always deal with fellow humans, or with creatures that have human-like emotions and motivations.

- Robot - Robots are quick, calculating, and equipped with many different tools to get them through their tasks. They particularly excel at hacking and electronic warfare. They are also very good with guns, favoring long-range attacks over melee combat (where their fragile joints are a liability). They suffer socially, however, being handicapped by their historical status as slaves and servants, by their difficulty in understanding human emotions and motivations, and by their general appearance and demeanor. Robot cards should focus on different tools and settings to uplink with or disassemble anything that gives them trouble.

- Cyborg - Cyborgs are tough, powerful, with vast stores of knowledge they can access. They are often equipped for hacking, but it is more dangerous for them then for robots--electronic countermeasures can sometimes fry a cyborg's brain. Their enhanced speed and strength make them excellent at hand-to-hand combat. They can struggle socially in some circles--not all sentient beings approve of man/machine hybrids. Cyborg cards should focus on brute strength, bashing straight through trouble with little regard to consequences; also cards that can mitigate potential consequences, to represent the cyborg's toughness.

- Uplift - Uplifts are intelligent, yet retain their animal senses and instincts. It would be thematically useful to decide on a particular species for this Persona, such as dogs, cats, chimps, or pigs, but I don't want to commit to anything just yet. Uplifts are smaller than humans (or robots or cyborgs), making it easier for them to utilize the environment to their advantage. Uplift cards should focus on stealth play--hiding in small spaces, avoiding detection, using maintenance tunnels and air ducts to reach objectives, etc. Uplifts struggle with hacking, as the interfaces are always designed for human use. They can struggle in combat against prepared opponents, but stealthy attacks often allow them to subdue threats without a fight.

That seems good. Four different strategies--deck manipulation, finesse, brute force, and stealth. Hopefully they will combine well to create a wide variety of deck types.

Now, once the decks are crafted and the game has begun, most of the decision-making will take place during encounters. So we really need to get those RIGHT. What do encounters look like? What sort of information is presented to the player? What tools will they have at their disposal to overcome the encounters?

The current plan is to have semi-linear stories that introduce random encounters. Let's brainstorm some RE ideas to make sure that we can include encounters that play to each Persona's strengths and weaknesses.

- Locked Door

- Machine Gun Turret

- Malfunctioning Bridge Extension

- Robot Sentry

- Sniper on the Ridge

- Guard Post

- Angry Mob

- Crafty Salesman

- Indifferent Pilot

- Bounty Hunters

- Data Storage Unit

Well, the good news is, I can come up with plenty of ideas for problems that the player must overcome. The BETTER news is that the problems tend to break down into one or more categories:

- Combat - The player must fight someone or something. They may not need to kill or destroy their opponent, however; sometimes they can merely subdue it. Since I'm very much a life-affirming person, I like the idea of providing cards that accommodate a no-kill strategy. Stun guns and tranq darts all the way!

- Hacking - Sometimes the player must interact with computer terminals. Maybe they have to hack some bots, turrets, or security cameras. Maybe they have to dig up some information from a data storage unit. Maybe they have to scramble the coordinates before some missiles are launched. There are a lot of interesting ways this could be incorporated into the story.

- Social - Occasionally the player will have to deal with people, not all of whom will want to deal with them. Maybe they need a component or weapon that they can only get from a black market dealer. Maybe they need to calm an angry mob before someone gets hurt. Maybe they must bribe a pilot to take them somewhere discretely. Whatever it is, some Personas will have an easier time than others.

- Environmental - The door is locked! The bulkhead is leaking! The bridge won't extend! The forest is freaking ON FIRE! There are a lot of ways to force the player to overcome obstacles presented by the environment, some of which will require some fast-thinking, some of which will require brute force.

It's looking more and more like some of the encounters within the stories will or should be pre-scripted. They will be the same every time. I'm okay with that. It's a good way to provide narrative structure. There can still, of course, be plenty of random encounters, as well.

It's interesting that there are four Personas, and four encounter categories. This makes me wonder if perhaps the different Personas are adept at different categories. Let's see if we can rank each Persona and how good it is at dealing with the different types of encounters.

That seems to work, mostly. Some of those numbers are a little difficult to justify, though. For example, why is the Cyborg Persona the weakest at overcoming Environmental obstacles? Busting through locked doors or climbing up cliffs shouldn't be difficult for a cyborg. I do think that it's appropriate for Humans to not be great at hacking--after all, the average untrained human would have a hard time interfacing with and manipulating unfamiliar computer systems.

Still, this does give us a rough guide of what we can expect. Perhaps, for balancing purposes, the important thing should be that each Persona's total should be 10. So the Cyborg might actually be Combat 3, Hacking 3, Social 2, Environment 2. The Uplift might be Combat 1, Hacking 1, Social 4, Environment 4. Et cetera. But this does illustrate the relative strengths and weaknesses of the Personas. That will come in handy when we start brainstorming the actual cards.

This was a very useful session! I think the next step will be to outline a rough story, including some encounters, and then working on cards for each Persona. Then we can stress test the system and start hammering out the rules.

Saturday, August 10, 2013

Brainstorming for the 2013 Solitaire Print and Play Contest

This year's solitaire game design contest has begun, which means I have a few short weeks to prepare and submit a game. I was originally planning on submitting Horns of Thunder, the sequel to my well-received solitaire story game Wings of Lightning. However, I've had a lot of thoughts banging around in my head about how to integrate story and game mechanics, and wanted to put it all on paper. This post is a massive brainstorm, and will subsequently be long and somewhat incoherent. However, it may be useful for some people to see a designer's mind at work. Or this will just be really boring--I've no idea.

- I'm really intrigued by the idea of using a customizable deck of cards to work through a gamebook. So there might be two to four pre-crafted decks for players who just want to dive in, or the player could build his or her own deck.

- To keep the decks roughly thematically appropriate, I'd probably borrow the idea of Influence from Android: Netrunner. The players would have a particular Identity or Persona that have a particular set of cards associated with them that they can include at no cost. However, all cards would be marked with an Influence cost, and each Persona could only include out-of-character cards up to their Influence limit.

- For example, the Human character could only include a limited number of cards from the Cyborg deck.

- One of the reasons this idea appeals to me is that I can release expansions--new stories to overcome, new Personas, new cards for the different Personas, etc., all within the same rules system. Heck, I'd be more than willing to open the system up to all users, so that they can generate their own stories, Personas, and cards!

- The catch is that I have to get the system right. Once it's released, it will be much more difficult to go back and fix any problems inherent in the rules set.

- So let's think about the AI. What sort of challenges will the player have to overcome, and how will the game react to the player's decisions?

- I like to approach these sort of problems from a thematic perspective. So I'll start with a case study.

- Say the player is traversing some rocky terrain and stumbles across a goblin campsite. The goblins haven't noticed her, yet, but she's not confident that she can skirt around them. She has to go through them.

- What are her options?

- She could fight them, risking her life and probably taking some wounds

- She could frighten them, causing them to scatter.

- She could set up a distraction, and hope they abandon the camp to investigate long enough for her to sneak past.

- She could reveal herself and talk to them, hoping to persuade them to let her pass.

- Could I just keyword the encounters? So with the example above, the player must discard an appropriate number of Fight, or Frighten, or Distract, or Talk cards to progress?

- That's stupid; that's basically just asking whether the player has the right key or not, which does not make for compelling gameplay. I want the player to have to make difficult decisions.

- What if the encounters didn't spell out how to overcome them? It could be up to the player to decide how to use the cards at his or her disposal. So a card might say, "Distract +3." The player would use it, hoping that a distraction would work on the encounter. He or she would then look at the current paragraph number, add three, and consult that paragraph. So, if he or she was at Paragraph 24, he or she would proceed to Paragraph 27. If it said "Distraction Successful," the card worked.

- That doesn't work, either. First of all, that would require a massive amount of work on my part just to create a small story. I'd have to account for half a dozen or more permutations for each encounter. That's a lot more writing for a small gain. Plus, he player would have little to no basis for his or her decision. What if the player decided to Frighten the goblins, but it failed? How would the player no it was going to fail? What hints could the system give that one option was better than another? What sort of consequences would there be for failure?

- No, that's way too much work for me and not enough fun decision-making for the player. I'll have to find another solution.

- On top of which, I'm not sure I want the story to consist of numbered sections. Would it be possible to have a slightly more linear story, with random encounters scattered throughout? How would that look?

- So the player is going along, reading the story, and he or she hits a Random Encounter. He or she then rolls on a chart based on his or her location, and perhaps some other factors adjust the die roll. The chart then tells the player what sort of encounter he or she must face. He or she deals with it, suffers some consequences, gains some bonuses, and proceeds with the story.

- That could theoretically work. In fact, I like the idea that the story would have a general overall shape, but with little crests and valleys and twists that are with each play through. I could even have some branching paths that would only be accessible based on particular random encounters happening at particular points in the story. That could be fun.

- Okay, so I've got a basic story structure. But how do random encounters actually work? What information is given to the player when they hit a random encounter? And will I be able to have encounters that are not purely combat-based, so that players can work through the story in a number of different ways that don't involve the murderation of dozens of animals and sentient beings?

- Let's say that the player rolls an encounter. That encounter might have several different stats indicating how one MIGHT overcome it, and the player can use his or her cards to match or beat one of those stats.

- So the goblin encampment would have Fight 15, Frighten 20, Distract 9, and Talk 12. The player would have to muster up enough Fight, Frighten, Distract, or Talk cards to overcome one of those options. Otherwise, the encounter gives a certain consequence.

- That's still a bit too much like needing the right set of keys to get through the door. I don't like the fact that the player knows EXACTLY what he or she needs to beat the encounter.

- Is there some way to "hide" the exact numbers that the player will need to overcome? That way I could merely hint at what the player needs, but he or she would be uncertain about whether his or her Lighting Strike and Dual Wield Daggers (Fight 9 and Fight 6, respectively) would be enough to get through the goblins.

- I know! I could randomize the stats. So instead of "Fight 15, Frighten 20," etc., the player would see "Fight 2d6 + 6, Frighten d12 + 4, Distract d6 + 1, Talk 2d6 - 2." The player would assemble his or her response to the encounter, THEN roll to see if he or she defeats it. That adds a nice push-your-luck element that I think could really work.

- The best part is, sometimes the player will KNOW that the dice cannot possible roll high enough to defeat his or her response, but sometimes the player will be forced to gamble on a low number in order to conserve resources.

- Plus, I could have the story branch out in different ways, depending on how the player overcame the random encounter.

- Yes, I like this a lot! It's potentially very compelling, and can reward players for progressing through the game in multiple ways. Replayability is always good for a solitaire game, especially one with a customizable component like the player's deck.

- Now to think about theme....

- This system could obviously translate very well to a fantasy theme. The player could be a mage, a soldier, a noble, or a merchant, with different strengths and weaknesses against different kinds of encounters.

- The problem with fantasy is not only that it's been done a lot, but it's been done WELL a lot. That's a lot of pressure to compete!

- I'm not sure I'm interested in a modern thriller or spy story, but it could work. Something to keep in mind.

- Sci fi would be fun, though. I love a good sci fi story. And this system could let the player play in the universe in fun ways. A human, a cyborg, an uplifted animal, and a robot would all interact with the encounters in different ways. The robot might be prone to hacking and electronic warfare, while the cyborg uses brute strength and enhanced speed to bring down his or her enemies. The human is relatively weak and fragile, but overcomes many different types of obstacles through creativity and ingenuity. The uplift has certain social obstacles and advantages, as an animal living in a world designed for humans, but is a master of stealth and surprise.

- Yes, I like this a lot! I think I'll go with it.

- Now, let's consider what a deck actually looks like.

- I like the idea of smaller decks. The players shouldn't need a 60-card monstrosity to get through a story. Let's say a 30-card minimum deck. Probably a maximum of 3 copies of any given card. That makes printing easier--my card sheets are 3x3, so I can put three copies of three unique cards per sheet.

- I also like the idea of giving the player actions to take outside of what is explicitly written on the cards. So while the Human player might have a card that he or she can discard to draw three additional cards, or to search his or her deck for a particular card, all Personas will have the option to, say, discard a card to draw a card.

- I don't think I want the player to have to deal with his or her own stats, not even Health or Oxygen or anything like that. Everything he or she needs should be in the deck or in the encounter tables. It's just simpler that way. So what sort of punishment can the AI dish out?

- Perhaps running out of cards in the deck means death? No, that would reward players for playing huge, bulky, cumbersome, extremely random decks. I think I'll allow the player to shuffle his or her discard pile into a new deck when the deck runs out.

- Hand size, then, could be the player's Life. Take damage, discard a card. Run out of cards in hand, and you're dead.

- The problem with that idea is that a player could get into a death spiral. He or she doesn't have enough cards to overcome a particular encounter, so he or she takes damage, so he or she has fewer cards to deal with the next encounter.... So that doesn't quite work, either.

- What about removing cards from the game permanently? Take damage, exile the top card of your deck. That card is gone forever; I don't care if it's a really strong card, you don't get to use it this game. Hm... maybe. I don't like the fact that it won't always FEEL like damage. "Oh, I don't really care about that card, so that encounter wasn't very punishing at all."

- Maybe a mixture of those ideas? Some encounters force you to discard cards from your hand if you fail, which limits your options. Some of them force you to exile cards from your deck, which CAN limit your options. And some of them could put a cap on your hand limit, so you don't necessarily have to discard cards, but now you can only ever hold 4 cards in your hand instead of 5. So when you draw cards, you'll occasionally be forced to discard cards.

- I also think it's important to keep the player from just digging through the deck for the exact cards he or she needs for every encounter. So there should be a penalty for having to shuffle your discard pile to create a new deck. Perhaps, if you run out of cards in your deck, you shuffle your discard pile into a new deck, then exile the top two cards? So each time you have to reshuffle, you have fewer and fewer cards left in your deck. Yes, that should work. It's not too punishing initially, but if the player abuses that strategy, he or she will find him or herself without many options.

- Okay, I'm really liking this idea. Time to go brainstorm some cards, and to sketch out an outline for the first story!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)